Our site is customized by location. Please select the region of your service and we’ll remember your selection for next time.

Select a region for customized content and rates

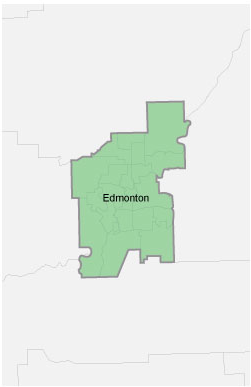

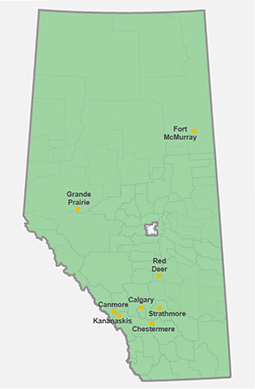

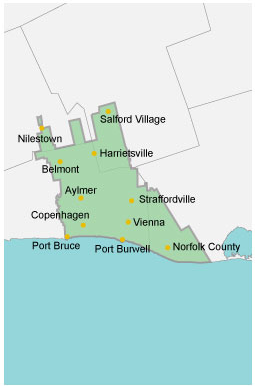

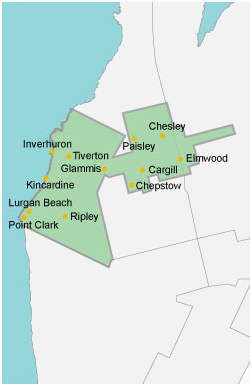

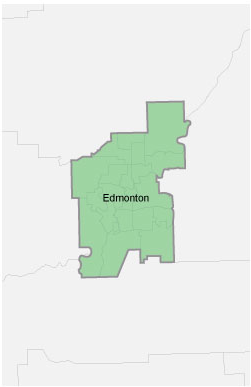

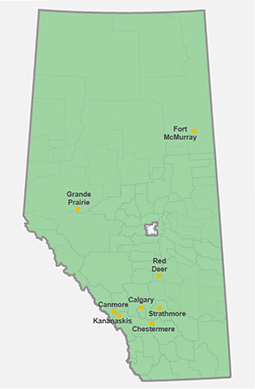

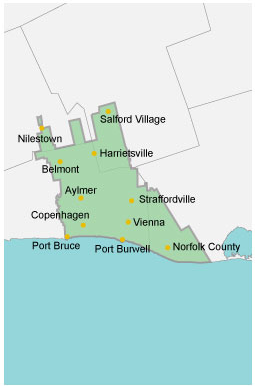

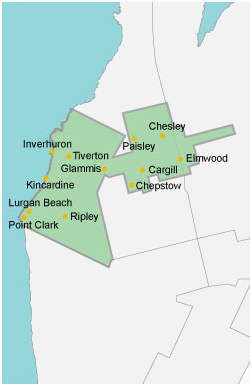

Looks like you're in Canada

Looks like you're in the United States

Select a region for customized content and rates

Select a region for customized content and rates

Select a region for customized content and rates